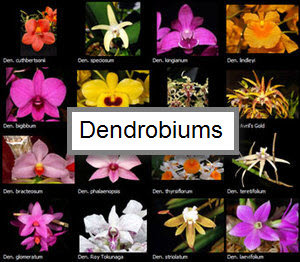

Dendrobiums Offer Myriad Choices in Plant Size and Flower Color

ONE OF THE LARGEST AND MOST diverse of orchid genera is Dendrobium, with various authors listing the number of species from about 1,000 up to as many as 1,500. They extend across a wide range from India to China and Japan. Dendrobium orchids are also extensive through Malaysia, the Philippines and Pacific Islands as well as Australia and New Zealand. The largest number of species occurs in Papua New Guinea.

The genus Dendrobium is derived from the Greek words dendron, for tree and bios, meaning life. The name refers to the epiphytic nature of most species and might loosely be translated into “tree dweller.” As one might expect with such a large group, not all species are epiphytes. Some are lithophytic and a few terrestrial.

Dendrobium species and hybrids often have rather large, showy or colorful flowers that make them popular among orchid growers. Most collections con-tain at least a few. The genus also includes some examples with unique and bizarre flower forms. The common denominator among them all is a mentum or “chin” that most have at the back of the blossom where the lateral sepals join the foot of the column. In some cases, it is extended into a short spur.

Many dendrobiums have rather long, slender stems with nodes along them. These stems are popularly referred to as canes. Dendrobium foliage may be evergreen or deciduous, depending on the species. Culturally, dendrobiums are com-monly said to do best in bright light. Experienced growers will generally recommend keeping most of them rather tightly potted in a fast-draining medium, or cultivating them on mounts.

Further generalizations about dendrobiums are difficult. There are robust large types as well as dainty miniatures. Some produce their flowers singly or in small clusters of two or three while others sport inflorescences that may contain dozens of blooms. Flowers of some types last a few days, yet others remain attractive for a few weeks.

While most do best with moderate to high levels of relative humidity and, like most orchids, benefit from good air circulation, temperature requirements vary considerably depending on a particular dendrobium’s native habitat. There are types that require cooler growing conditions as well as those that thrive in intermediate to warm environments. Many dendrobiums need seasonal variations in temperature in order to grow and flower successfully. Some tolerate regular watering throughout the year, yet quite a few demand a dry rest period before they will produce buds.

Perhaps because of the variety of growing requirements within this sizeable genus, dendrobiums have an undeserved reputation among some as being difficult orchids to flower. The problems in getting a dendrobium to rebloom are usually related to un-derstanding its seasonal temperature and moisture needs. It is important to do your homework before you add a particular dendrobium to your col-lection to assure that you understand and are able to provide the growing conditions it requires.

Cane-type dendrobiums will oc-casionally produce plantlets or keikis on their stems. Some growers attribute the production of these to adverse growing conditions, such as too much moisture or excessive temperatures. These small plants may be removed from their parent and planted on their own after sufficient roots have developed. Most types of dendrobiums may be propagated by division as well.

Taxonomists have often divided this massive genus into subgenera and further into sections within each subgenus in order to group together species with obvious similarities. A look at a half dozen of the larger and more commonly encountered sections within the genus may help point out some similarities in the appearance of the species within them as well as a few commonalities in their cultural needs.

SECTION DENDROBIUM Among the most familiar and popular dendrobiums are the species and hybrids that are often referred to as soft-cane dendrobiums, taxonomically known as Section Dendrobium. This group includes such familiar species as Den-drobium nobile, Dendrobium parishii, Dendrobium anosmum, Dendrobium loddigesii and Dendrobium fimbriatum, among others.

Stems in this group are generally slender and fleshy and may grow rather erect and canelike or be quite pendulous. Two ranks of leaves grow along the stems, alternately at each node and last for a growing season or two.

These are perhaps the most familiar of all dendrobium flowers and are often the first that come to mind when the genus is mentioned. Blossoms are generally produced on short inflor-escences with one to three flowers. In most species the flowers appear primarily on the plant’s older, leafless canes. In the case of some hybrids, the blossoms are so numerous that they create a column of floral display much of the length of the cane. This group of dendrobiums is widespread across much of southern Asia and extends to Korea, Japan and Borneo as well.

Species and hybrids of the soft-cane dendrobiums have some cultural demands that vary with the seasons. Most grow actively in spring and summer and should be fertilized and watered generously from the time new roots appear until the last leaf of each new cane matures. At that time continue to provide plenty of light but withhold water and fertilizer and reduce the night temperatures to 50 F (10 C) or lower until flower buds appear in winter or early spring.

SECTION FORMOSAE The species in Section Formosae comprise another popular group of dendrobiums. These are the nigrohirsute or black-haired dendrobiums, so called because of the short dark hairs found on the leaf sheaths along their canes. The canes generally grow upright and the foliage is often shiny.

Flowers in this group are typically white, often with yellow or orange markings on the midlobe. The sepals (and sometimes the petals) may taper to a stiff point, giving them a pristine starry appearance. The blossoms are sometimes fragrant, tend to be long-lasting and are produced in small clusters of one to three among the leaves of the plant.

These dendrobiums range across India to Thailand, China, the Phil-ippines and Borneo. Many species in this section thrive in intermediate conditions and grow more or less continuously through the year. As this is a fairly large group, check the recommendations for individual species carefully, as some of them come from cooler habitats, others from warmer regions. Regardless of origin, a brief cooler, drier rest period is required by a number of them.

Numerous attractive and rather easily grown hybrids have been derived from members of this group. Among them are Dendrobium Dawn Maree (formosum × cruentum), Dendrobium Frosty Dawn (Dawn Maree × Lime Frost), Dendrobium Green Lantern (Dawn Maree × cruentum), Dendrobium Formidible (formosum × infundibulum), Dendrobium Iki (bellatulum × cruentum), Dendrobium Fire Coral (cruentum × Formidible) and Dendrobium Judith Nakayama (Dawn Maree × Formidible).

SECTION CALLISTA For den-drobiums with high-impact inflor-escences, you can hardly do better than certain species that are found in Section Callista. Some boast pendent racemes of flowers that resemble clusters of grapes; others have fringed lips or petals. Regrettably, some of these dramatic dendrobiums have flowers that do not last as long as those of some of their cousins, but they are nevertheless well worth the effort.

This group often produces rather plump, bulbous canes that are narrow at the base. The foliage is often crowded toward the tips of the canes. Most species occur in mountainous areas of southern Asia from Myanmar (Burma) to southwestern China. To generalize, they need intermediate to warm conditions when in active growth during the summer months, followed by an extended cool, dry rest period. At this time, water the plants little, if at all, until flower buds begin to appear in spring.

Dendrobium farmeri is one of the most beautiful of the species, sporting pendulous clusters of flowers. Its rounded blossoms are typically white to pale pink, with a golden lip. Their shape, coloration, and perhaps the time of year they bloom frequently remind me of certain small flowered narcissus.

As the species name indicates, the flowers are even more closely arranged on the pendent inflorescences pro-duced by Dendrobium densiflorum. Its scented flowers are yellow with darker orange lips that have a fringed edge. Dendrobium thyrsiflorum has a similarly dense arrangement but the flowers are white, occasionally pinkish, with bright yellow lips. Some consider the latter a color variation of the former. Either may rather easily be grown into a specimen that is spectacular when in flower. And there is Dendrobium lindleyi, also known under the name Dendrobium aggregatum.

The fringed lip award in this section, however, would seem to be deserved by Dendrobium brymerianum, a somewhat uncommon species that I have not seen. Descriptions indicate that its racemes carry one to several rather large golden yellow flowers. Photographs show that its sepals and petals are not particularly broad, which seems perfectly logical when you see the effort this species exerts in producing a dramatic, branched fringe about the wide lip, reminiscent of Rhyncholaelia digbyana.

Similarly rare and remarkable is Dendrobium harveyanum. It has not only a light fringe around the lips of its golden yellow flowers, but a heavier fringe along the margins of the petals as well. Some taxonomists have more recently moved this species into Section Dendrobium.

SECTION PHALAENANTHE Although Section Phalaenanthe includes a comparatively small number of Dendrobium species, they are probably familiar to many because of their economic importance to the cut-flower trade. Even within this small group there is some disagreement among taxonomists as to exactly how many species there are. These orchids are native to Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and northern Australia.

The canes of this group are long and narrow or slightly spindle-shaped. Leathery foliage appears toward the ends of the canes, which is also where the inflorescences, often elongated and bearing many flowers, emerge.

The flowers of the species are large and sport petals that are considerably wider than the sepals. One of the most familiar species is Dendrobium phalaenopsis (syn. bigibbum). These and their hybrids are typically colored white or purple as well as a range of color combinations in between.

In nature, the species in this group are said to be found in high light and warm temperatures when in active

growth, followed by a definite dry period following flowering. Commercially cultivated hybrids, however, seem to have been developed such that they are productive for much of the year.

Floral designers frequently use sprays of these orchids in their arrangements as well as wedding boquets. These blossoms are often the flower of choice in the making of Hawaiian leis, and they seem to frequently turn up as a garnish on plates in Thai restaurants as well — at least in the United States. More than one server at a Thai restaurant has informed me they are edible, and while I have ingested one or two with no ill effects, a salad of them alone, while beautiful, would not be relished by me.

SECTION SPATULATA For floral intrigue, some of my personal favorites are the antelope dendrobiums of Section Spatulata. I find the long, twisted petals found on many species in this group irresistible. That some of them carry those spiraling petals nearly upright seems to me to defy gravity in a unique and most curious fashion. The heights that the plants of some of these species attain seem to defy gravity too.

Many of them come from relatively hot, humid habitats in Indonesia, the Philippines and northern Australia. The evergreen foliage is often bright green, somewhat thickened and borne in two rows along fleshy long canes.

This group of dendrobiums is cultivated with little or no rest period. Their inflorescences are produced near the tops of the stems; they are frequently elongated and may bear several to many flowers. Some species bloom more than once a year and tend to be somewhat free-flowering.

If space is a consideration for you, look for Dendrobium antennatum, which usually reaches only about 2 feet (60 cm) in height. A loftier situation will be required for Dendrobium stratiotes, which generally ranges from 2 to 3½ feet (60 to 100 cm). If the sky is the limit (somewhat literally), you may have room to cultivate Dendrobium taurinum and Dendrobium lasianthera whose canes may extend to 9 feet (2.7 m) or perhaps even Dendrobium discolor (syn. undulatum) with lofty stems said to grow to as much as 15 feet (5 m) tall.

SECTION LATOURIA Similarly interesting are the curious blossoms produced by the Dendrobium species in Section Latouria. The flowers are often nodding, sometimes hairy and frequently have a twisted if not somewhat grotesque appearance.

Many species in this section are vigorous growers. Pseudobulbs are often swollen and much narrower at the base. The foliage emerges toward the apex and lacks sheaths. Most of these come from Papua New Guinea and nearby regions. The majority thrives in intermediate to warm conditions with high humidity and seemingly no rest period.

The king of the group is surely Dendrobium spectabile. In late winter or early spring, inflorescences begin to emerge just below the leaf bases of its 24-inch (60-cm) stems. Each will mature to carry a good number of truly bizarre blossoms. Sepals and petals are long, pointed and twisted; their margins considerably wavy. The flower color is generally creamy, but a large amount of maroon veining and mottling is often exhibited, particularly on the lip. These somewhat sinister-looking flowers never fail to elicit comment.

Much tamer in appearance are its cousins Dendrobium johnsoniae, Den-drobium atroviolaceum, Dendrobium forbesii and Dendrobium rhodostictum. These species and others have been crossed to produce a popular group of dendrobiums that is sometimes referred to as New Guinea hybrids. Examples include Dendrobium Roy Tokunaga (atroviolaceum × johnsoniae), Den-drobium Nellie Slade (atroviolaceum × forbesii), Dendrobium New Guinea (atroviolaceum × macrophyllum), Den-drobium Andrée Millar (atroviolaceum × convolutum) and Dendrobium Hermon Slade (New Guinea × rhodostictum). Many of these produce impressive long-lasting floral displays.

The genus Dendrobium offers a multitude of floral fascinations, making it one of the most interesting and fascinating of all genera in the orchid family.