A Rich History Awaits Those Who Look for Out-of-Print Volumes

IT IS NO SECRET THAT THE INTEREST and passion for orchids has led to numerous writings about them for many decades, and my weakness for collecting books has led to the acquisition of more than a few titles on the subject. While my personal orchid library includes several dozen volumes, I find that I most frequently reach for only a few of them. Here are some of my favorites, all of which happen to be out of print:

Wily Violets & Underground Orchids: Revelations of a Botanist, by Peter Bernhardt. 1989. (William Morrow and Company, Inc., New York)

This publication may be unfamiliar to many orchidists, since it is not exclusively about our favorite flowers. The book consists of a somewhat random but fascinating series of chapters relating the author’s botanical observations and experiences as well as interesting information about plant and animal relationships. He discusses an array of topics ranging from seasonally dry tropical forests to Australian botanical curiosities. He even includes an intriguing essay on the American prairie ecosystem.

Basically, this publication is a chronicle of the reproductive strategies and theories about various plant species, including discussions on violets, bromeliads and trout lilies, among others. The prose is easy to read and the author has a knack for explaining complex processes in relatively simple terms. A particularly thought-provoking discussion is of-fered regarding the variations among plants in their floral biology and how that affects the sort of pollinator they attract and their method of pollination.

If your plant interests are exclusively related to orchids, you should immediately skip to the last third of the book — chapter 13, to be exact. From here until the end of the volume, the author writes several chapters on orchid topics, including a lively chronicle of the 19th-century craze for tropical American orchids and an entertaining recount of the tale of Charles Darwin, Angraecum sesquipedale and its pollinator.

The book concludes with perhaps its most interesting chapter, which describes two odd species of elusive Australian subterranean orchids and how they survive.

A Manual of Orchidaceous Plants, by James Veitch and Sons. 1887–1894 (Chelsea, Great Britain)

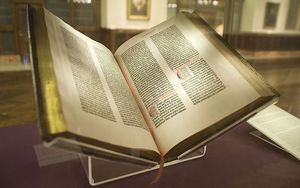

Many authors contributed to this landmark work on orchids that was originally published in the late 19th century. It is a two-volume work that has been reprinted a couple of times, but even the reprints command a dear price. This is a reference work, not something you will likely sit down and read from cover to cover. But it is truly a book you can return to time and again.

The nomenclature has changed for many orchids in the more than a century since it was written, but the book is full of anecdotal information and the prose seems infused with the ex-citement that the writers of the time had for these plants.

The illustrations are charming examples of some of the best line art of that time and would provide a treasure trove of legally reprintable art for any orchid society’s newsletter editor who needs to fill space. I find it curious to see how some of the illustrated species still look much the same today, while others are different, no doubt due to later discoveries and more than a century of inbreeding.

You may have to seek out a specialty library to find a copy of this one to browse. If you should happen on an affordable copy at an estate sale or used bookstore, grab it.

Growing Hybrid Orchids Indoors, by Jack Kramer. 1985. (Universe Books, New York)

ack Kramer is a prolific author on a variety of horticultural subjects, both now and during the indoor gardening craze of the 1970s and 80s. For some reason, this particular book became a favorite of mine when I first discovered orchids. It has the usual introductory pages and chapters on history and general cultivation of the plants, and, as the title implies, advice on where and how to grow orchids in the home.

What captivated me about it, however, was a feature found in the chapters that make up the last two thirds of the publication. These pages discuss most of the popular types of orchids and their cultivation. Within these chapters are lists of particularly recommended orchids, by name. I found this book at a time when I was buying orchid plants faster than I could remember them, and, as most orchid novices will attest, orchid nomenclature, particularly of the hybrids, can be dizzying.

Somehow, these lists offered me guidance and something to hang my hat on when I went orchid shopping and was faced with benches of plants and dozens of different names. The book was five or 10 years old by the time I found it, so some of the hybrids were already unavailable, but I sometimes found their progeny. If nothing else, I credit this book with stimulating my interest in the history and development of contemporary orchid hybrids.

Native Orchids of North America, by Donovan Stewart Correll. 1950. (Chronica Botanica Company, Waltham)

This is another scientific pub-lication, but a beauty. The work covers the species that occur north of Mexico. It includes the appropriate scientific references for the naming of each species and an explanation of the scientific name’s derivation. Common names and a botanical description are followed by remarks that may include habitat information, anecdotal stories and plant uses. Geographical distribution and cultural notes conclude the discussion of each species.

The botanical illustrations and line drawings are by Blanche Ames and Gordon Dillon. As an amateur artist, I find them breathtaking. I was fortunate to find my pristine copy of this book several years ago at a used-book store in Canada.

Novelty Slipper Orchids — Breeding and Cultivating Paphiopedilum Hybrids, by Harold Koopowitz and Norito Hasegawa. 1989. (Angus and Robertson Publishers, New South Wales)

This is a readable, well-written book by authors who have experience with and passion for their subject, as well as a talent for writing volumes in just a few pages.

Many paphiopedilum books tend to be the author’s taxonomic treatment of the genus. This book is something different and includes details and perspective on many paphiopedilum hybrids that you could not find anywhere else. It is an excellent source for gaining an appreciation of con-temporary trends in Paphiopedilum breeding as well as the history behind it. The authors do an excellent job of explaining the inheritance and expression of specific traits in certain hybrids. The book also contains plenty of good advice on successfully growing different types of paphs.

Cattleya Superior Parentages (2), edited by Rue-Chih Hsiang. 1987. (The Orchid Society of the Republic of China, Taiwan)

For those who like cattleyas (I have met few orchid lovers who do not) this book is almost certain to captivate. It consists of page after page of color photographs featuring Cattleya Alliance hybrids and species. The book’s introduction states that more than 1,200 photographs are included.

The floral portraits are arranged in sections for different types or colors of flowers, i.e., splash-petal flowers, yellow flowers, miniature flowers, etc. The text is minimal and is written in both English and Chinese. The photographs are identified with the name of the orchid and often include parentage, awards and the natural spread (in centimeters) of the flower as well. In many cases, the photographs are arranged so that you can quickly visualize the characteristics that a particular flower’s parent passed on to its offspring. Whether or not you are a fan of hybrid orchids, you cannot help but be impressed by the hybridizers’ accomplishments after leafing through these pages.

I have another similar book, Cattleya, the King of Orchids, which was published by the Japan Orchid Growers Association at roughly the same time. Both are somewhat pricey, but I know of no other books like them.

My preference for these particular books is not meant to imply that they are the best orchid books, or even the finest on their subject, although a couple of them arguably may be. That which draws us to reach for a volume time and again is enigmatic. I suppose my personal interests in the history of orchid hybridization as well as their natural history lead me back to these.

You may wonder why I would offer suggestions of books that are out of print. The perhaps obvious answer is that out of print does not mean unavailable. This kind of book is seldom casually discarded. There are dealers who specialize in good used books, and even some who specialize in used orchid books in particular. The Internet has made the search for obscure titles quite simple, particularly for those unwilling or unable to scour the shelves of used-book stores.

If you are not inclined to amass a personal library, look to the shelves of your orchid society’s library for these titles or others like them. College and university libraries where horticulture and botany are studied are other possible sites where you might browse through such tomes. Public libraries, obviously, are another option.

For many, the proliferation of electronic information has not replaced the pleasure and utility of books. No doubt there are many good contemporary titles on bookstore shelves, but you may be surprised to find that some of the best were written some time ago.